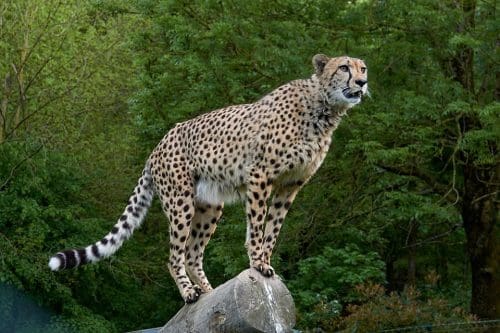

Cheetahs make a return to India, and the path goes directly to Kuno-Palpur National Park in Madhya Pradesh. Prime Minister Narendra Modi released eight cheetahs (five females and three males) in massive cages at Kuno on September 17, 2022.

The entrance of the big cats has put the hitherto undiscovered sanctuary on the world map. The cheetahs, the world’s fastest land mammal, were introduced to the park as part of an international translocation initiative to return the feline to India seventy years after it was proclaimed extinct.

Project Cheetah

The Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi released wild Cheetahs – which had become extinct from India – in Kuno National Park. Cheetahs – brought from Namibia – are being introduced in India under Project Cheetah, which is the world’s first inter-continental large wild carnivore translocation project.

The Prime Minister released Cheetahs at two release points in Kuno National Park. The Prime Minister also interacted with Cheetah Mitras, Cheetah Rehabilitation Management Group, and students at the venue. The Prime Minister addressed the Nation on this historic occasion.

The release of wild Cheetahs by the Prime Minister in Kuno National Park is part of his efforts to revitalise and diversify India’s wildlife and its habitat. The cheetah was declared extinct from India in 1952. The Cheetahs that would be released are from Namibia and have been brought under an MoU signed earlier this year. The introduction of Cheetahs in India is being done under Project Cheetah, the world’s first inter-continental large wild carnivore translocation project.

Cheetahs will help restore open forest and grassland ecosystems in India. This will help conserve biodiversity and enhance the ecosystem services like water security, carbon sequestration, and soil moisture conservation, benefiting society at large. This effort, in line with the Prime Minister’s commitment to environmental protection and wildlife conservation, will also lead to enhanced livelihood opportunities for the local community through eco-development and ecotourism activities.

The historic reintroduction of Cheetahs in India is part of a long series of measures for ensuring sustainability and environmental protection in the last eight years which has resulted in significant achievements in the area of environmental protection and sustainability. The coverage of Protected Areas which was 4.90% of the country’s geographical area in 2014 has now increased to 5.03%. This includes an increase in Protected Areas in the country from 740 with an area of 1,61,081.62 sq. km in 2014 to the present 981 with an area of 1,71,921 sq. km.

Forest and tree cover has increased by 16,000 square km in the last four years. India is among few countries in the world where forest cover is consistently increasing

Why Cheetahs Got Extinct in India?

According to the Union Ministry of Environment, the species was declared extinct in India in 1952, mostly owing to poaching and habitat degradation. In Madhya Pradesh, Maharaja Ramanuj Pratap Singh Deo of Korea killed the last three reported cheetahs in the nation in 1947.

Cheetahs were commonly utilised by hunters to track down and kill blackbuck. They were quite simple to train and manage for sport hunting. As per Divyabhanusinh, a well-known wildlife specialist, the use of cheetahs for hunting peaked during the medieval era, particularly under the Mughal empire. Throughout his rule from 1556 to 1605, Emperor Akbar himself possessed a number of 9,000 cheetahs.

The capture of wild cheetahs made breeding challenging and resulting in a population collapse well before British rule in India began. Forests were removed under the British administration to make way for towns and agricultural areas, resulting in the loss of species habitats.

Furthermore, there is an indication that Britishers regarded the creatures’vermins’ (destructive to crops, farm animals, or wildlife, or carrying sickness) and began giving monetary awards for shooting them beginning in 1871.

Why Kuno-Palpur National Park selected?

Kuno was chosen from a list of six probable sites, including Rajasthan’s Mukundara Tiger Reserve Rajasthan and Shergarh Wildlife Sanctuary, as well as Madhya Pradesh’s Gandhi Sagar Wildlife Sanctuary, Madhav National Park, and Nauradehi Wildlife Sanctuary.

According to reports by Nature in Focus, Kuno and the surrounding region were once great cheetah habitats and a major place for their hunting during the Mughal Empire. The sanctuary has prepared well to receive eight cheetahs that were previously released in large cages.

JS Chauhan, the Principal Chief Conservator of Forest (Wildlife) of Madhya Pradesh, who is directly involved with the cheetah restoration initiative, expressed confidence that the relocation plan will be a huge success.

He claimed that Madhya Pradesh had mastered the art of wildlife conservation and animal species regeneration, mentioning the Panna Tiger Reserve as proof.

Therefore, in Madhya Pradesh’s Kuno National Park, eight Namibian Cheetahs were released in specially prepared Bomas. It was done by flying to Gwalior airport and then airlifting to Kuno National Park. They were then released into a specially built cage for a two-month quarantine. During this time, their movements, food, adaptability, stress level, and other factors will be thoroughly watched and recorded by a specialist team. Cheetahs were transferred to open forests in phases after they were confident that everything was going as planned.

Cheetah movements are being tracked by experts. All the cheetahs are in good health, active, and adapting well to local conditions. According to specialists, they were given buffalo meat, adding that the felines were pleased and in high spirits in their new habitat. These creatures are said to eat once every three days.

Their high health and comfort level in India is also a testament to the Project Cheetah team and foreign experts’ attentive care, monitoring, and controlled activities. This initiative is part of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s attempts to revive and diversify the nation’s biodiversity and environment.

Also, cheetahs are secure and safe (in the bigger enclosure). The cheetahs will become acquainted with various woodland trees and prey bases here. They don’t have to be on the lookout for wild animals for the next three months, particularly 45 leopards in the region.

Let us now learn more about Kuno Palpur National Park

Kuno National Park in Madhya Pradesh, which has become home to cheetahs after a 70-year absence, is a one-of-a-kind attraction for all nature enthusiasts and aficionados. When one enters this park, they are greeted by the special forest of Kardhai, Khair, and Salai, as well as dozens of creatures foraging throughout huge meadows. Few of the grasslands here are larger than those witnessed in Kanha or Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserves. The best time to visit this national park is October-June.

Kuno National Park, which is mostly characterized by Kardhai, Salai, and Khair trees within mixed forests, is home to a diverse range of floral and faunal biodiversity.

It has a diverse ecosystem with 123 tree species, 71 shrub species, 32 species of climbers and exotic plants, 34 kinds of bamboo and grasslands, 33 species of mammals, 206 types of birds, 14 categories of fishes, 33 species of reptiles, and 10 amphibians of various species. With so many floral and faunal lifeforms, it is one of the most biodiverse places in the Central Indian geography. It is popularly thought that the Kardhai tree, which grows abundantly here, turns green even in the absence of humidity in the environment prior to the first monsoon rains arrive.

In plenty of other ways, it embodies Kuno’s genuine character, with its never-say-die attitude and capacity to endure and eventually develop despite the numerous obstacles this forest has faced.

This region, which is now a National Park, began as a 350 sq km reserve. And it was in the shape of a leaf, with the Kuno River creating the main backbone of the heart. This river serves as a lifeline for the wildlife refuge and provides scenic views of nature. This river not only keeps a consistent water supply in the region and irrigates the forest from the inside but also provides this protected territory with its identity.

Seeing as the project of reintroduction of Asiatic Lions has been continuous for some time, and one of the necessary conditions highlighted by concerned authorities about the standing of this nature reserve as a Sanctuary not being deserving of organising the lions, it was improved to National Park while contributing another 400 square km, making it a total of 748 square km of pristine forest area. The park is part of the larger Kuno Wildlife Division, which covers an area of 1235 square km.

Since prehistoric times, the region encompassing the Kuno River has been rich in wildlife. Its significance may be seen in the 30,000-year-old cave paintings representing various wild creatures in adjacent Pahargarh.

Recognizing the importance of this location, the Madhya Pradesh government set up the Kuno Wildlife Sanctuary of around 345 square km within a wider forest area of roughly 3300 square km in 1981. Therefore to boost wildlife protection and ensure effective administration of this region, an additional 891 square km were later introduced as a buffer to construct the Kuno Wildlife Division of 1235 square km in 2002.

This area is biogeographically part of the Kathiawar-Gir dry deciduous forest eco-region, and the forest types identified there constitute Northern tropical dry deciduous forest, Southern tropical dry deciduous forest, Dry Savannah woodland & grassland, as well as Tropical riverine forest.

It is similarly rich in faunal species, providing a unique combination of numerous beneficial elements for biodiversity. The prominence of this place is reinforced by the fact that the Wildlife Institute of India identified it as the perfect setting for the Lion Reintroduction Program in its assessment due to its suitability in several aspects.

Once the region was recognised as the most convenient spot for Asiatic Lion reintroduction, the then management began making long-term focused efforts to upgrade this area following the requirement, commencing with migrating the villages from within the park to a destination that is more advantageous to the inhabitants of those villages as well as the dwellers of the forest areas. From 1998 to 2003, 24 settlements were resettled outside the reserve, freeing up around 6258 hectares.

With the park’s management body’s coherent and ascertained attempts, resettlement of villages resulting in reduced biotic stress and advancement in floral, faunal, and avifaunal density in the park, the Government of Madhya Pradesh updated the condition of this region, enhancing it to evolve into a National Park with 748.761 square km as the central part and 557.278 buffer neighbourhood as the buffer in December 2018. The designation of Kuno Sanctuary as a National Park further emphasises its significance in the field of wildlife conservation in the Central Indian surroundings.

Kuno National Park contains both northern and southern tropical dry deciduous forest, as well as riverine woodland, savannah, and grasslands. Kardhai, Salai, Khair, and other important trees may be found here. Apart from reptiles, amphibians, and fish, the richness of its topography and vegetation has made it home to numerous species of animals and birds. Spotted deer, sambar, nilgai, jackal, wild boars, and other significant faunal species

The park has three entrances: Ahera, Tiktoli, and Peepal Bawadi. Gwalior, Shivpuri, Kota, Jaipur, and Jhansi are some of the closest transportation hubs to Kuno National Park. The distance varies according to the gate you are attempting to reach.

Although many animal fanatics are eager to go on a “cheetah safari” when it begins, the entire impact of the initiative will not be understood during the next few years.

Information on Cheetah Reintroduction Project in India

In India, the species became extinct in 1952. India then promised to reintroduce cheetahs in a number of areas, including Madhya Pradesh’s Kuno National Park, where personnel has been taught, many dogs have been qualified, habitats have been rebuilt, and huge predators have been relocated.

In 2009, Indian communicators, alongside CCF (Cheetah Conservation Fund), Bruce Brewer, Laurie Marker, and Stephen J O’Brien, pioneered the notion of Cheetah restoration. They continued to travel to India and have had advisory sessions with the government throughout the last 12 years.

The Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF) is a non-profit organisation dedicated to conserving and rehabilitating cheetahs across the globe. Its headquarters are in Namibia.

Eventually, in 2020, India’s Supreme Court accepted Project Cheetah as a pilot scheme.

In July 2020, India and Namibia agreed on an MoU (Memorandum of Understanding) indicating Namibia’s willingness to give eight cheetahs to India as the program’s inaugural component.

Read More: Latest